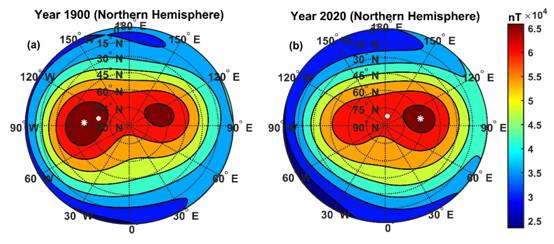

Earth’s magnetic field, a protective shield created by the planet’s core, is quietly changing. This invisible force field, which helps guide compasses and protect us from harmful solar winds, has been shifting for over a century. Scientists noticed that the north magnetic pole, which used to be nestled in Canada, till 1990, had slowly but steadily drifted toward Siberia. By 2020, it was moving at a surprising speed of about 50 kilometers per year. While this might sound like a minor geographic adjustment, the shift had significant consequences for the way charged particles behaved in space.

In Earth’s magnetosphere, a region called the radiation belts, hold energetic charged particles like protons and electrons. These particles, influenced by Earth’s magnetic field, gyrate, bounce, and drift around the planet. But where these particles end up—and how close they get to Earth—depends on the strength and shape of the magnetic field. Scientists have been trying to investigate how does the movement of the north magnetic pole change the paths of these particles.

Researchers at the Indian Institute of Geomagnetism, an autonomous institute of the Department of Science and Technology (DST) decided to simulate the trajectory of these particles using simulation models. They simulated three-dimensional relativistic test particles based on the IGRF-13 (International Geomagnetic Reference Field) model, to quantify changes in the altitudes of energetic protons.

Ms. Ayushi Srivastava, Dr Bharati Kakad, and Dr Amar Kakad discovered that in the year 1900, particles near the Canadian region, where the magnetic field was stronger, tended to stay at higher altitudes. But by the year 2020, the story was different. As the north pole shifted toward Siberia, the magnetic field in Canada weakened while the field in Siberia grew stronger.

According to the study published in the journal Advances in Space Research, this shift,disallowed particles over Siberian longitudes to dive deeper into Earth’s atmosphere. For some particles, the lowest altitudes they could reach (called penetration altitudes)rose by as much as 400 to 1200 kilometers over Siberia. This is because the stronger magnetic field gradients in Siberia created by the north magnetic field drift interacts with the ambient magnetic field and creates a force, which alters the trajectory of the charged particles. As a result, the particles are deflected outward, effectively preventing them from approaching the Earth in the Siberian region.

Such impact of geomagnetic field variations on particle dynamics, have real-world implications. Satellites in polar orbits, which pass through these regions, can experience varying levels of drag (resistive force caused by change in atmospheric density due to heating cause by collision of high energy and atmospheric particles) depending on how deep charged particles penetrate the atmosphere. The energy these particles deposit can also heat the atmosphere, changing its density and affecting satellite paths.

Source (PIB)